The fallout from the Post Office Horizon scandal: legal professionals under fire

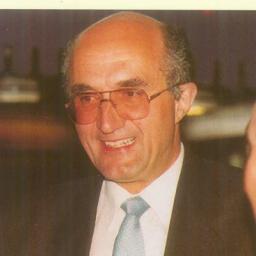

Dr Stephen Castell discusses the need for due accountability and redress from the legal professionals who were responsible for the Post Office Horizon miscarriage of justice

Over a 20-year period, solicitors, barristers and judges were involved in pursuing through the courts the Post Office’s (PO) private prosecution of hundreds of innocent victims, based on unchallenged evidence from the faulty PO Horizon software system, the biggest miscarriage of British justice. Those lawyers were professionally negligent, in dereliction of their duty, under clear court and practice rules, to ensure that all relevant computer evidence relied upon at trial should be fully disclosed, and available for expert examination and potential rebuttal.

Is a group litigation for a class action lawsuit the only way to bring those to blame effectively to account? What the PO Horizon scandal has graphically shown is that, in a world now utterly dependent on complex software systems, it is vital that lawyers are trained to be aware and make certain that at trial full disclosure of relevant computer evidence always diligently takes place. The technically complicated nature of such digital evidence must be faced, understood and engaged with by solicitors, barristers and judges, and not dodged – as it so negligently was in the faulty PO Horizon trials.

Introduction – the faulty ‘presumption’ concerning computer evidence

The 20-year PO Horizon miscarriage of justice was made possible through unchallenged reliance by the PO’s lawyers on the ‘presumption of the reliability of computer evidence’. However, that legal presupposition of the trustworthiness of computer evidence is, and always was, fundamentally incorrect. It arose through a misunderstanding and distorting by the Law Commission of the recommendations that I set out in my 1980s Verdict and Appeal Studies for HM Treasury into the legal and evidential reliability and security of computer software systems and technology (published as Castell, S., 1990, The APPEAL Report, May, Eclipse Publications, ISBN 1-870771-03-6).

Following my recommendations, the admissibility of computer evidence in court was introduced into law by way of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) 1984 (before that, such evidence risked being inadmissible and/or treated as ‘hearsay’). That was later mangled by the Law Commission into its 1999 ‘legal presumption of the reliability of computer evidence’ (see for example Christie, James, 2023, ‘The Law Commission and section 69 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984’, 20 Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review 62 – 95). This faulty forensic equating of ‘reliability’ with ‘admissibility’ was entirely at odds with the professional expert conclusions and recommendations of my carefully researched HM Treasury studies. Indeed, from the early 1990s onwards, in published journal articles, I have consistently said “A trial relying on computer evidence should start with a trial of the computer evidence” (see for example Computer Weekly, 22 December 2021).

The professional duty to disclose all evidence on which a litigant relies

However, it’s worse than that – and the Law Commission had no hand in a separate and distinctly egregious professional dereliction of duty by lawyers involved in pursuing those trials on behalf of the PO. Reliance by the PO’s lawyers on the infamous ‘presumption’ did and does not excuse that, in those hundreds of appalling private prosecution trials pursued against innocent sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses, there were no substantive or successful submissions made by the lawyers involved that the computer evidence on which the prosecution relied must be disclosed, for examination, challenge and potential rebuttal.

Indeed, if proper disclosure of all relevant evidence had taken place, it should surely have included the secret recordings recently reported as indicating that former Post Office CEO Paula Vennells knew about issues with the Horizon IT system at the same time as staff were being prosecuted, having been present at a meeting in 2013 suggesting she was made aware of reports that sub-postmaster accounts could be accessed remotely – warnings that were given to the PO by independent forensic accountant investigators from Second Sight. A PO lawyer can apparently be heard on the recordings confirming, “She knows about the allegation”. Responding to the tapes, Lord Arbuthnot, long-time campaigner on behalf of the victims, reportedly commented, “Very, very serious retribution needs to be visited on these people who visited such terrible things on the Sub-postmasters […] which should be dealt with by prosecuting authorities and by a judge and jury”.

Why did that full computer evidence disclosure not happen, when there is, and always was, a fundamental duty to disclose at trial all relevant – in this case pivotal – evidence, documentary or digital, on which a party relies? That duty arises under Part 31 of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) 1998 for civil cases, and also, as Andrew Marshall, a partner at Edmonds, Marshall, McMahon, has noted, under the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (‘Private prosecutions after the Post Office scandal’, Solicitors Journal).

The answer is that, undeniably, it can only have been the lawyers, who are always professionally responsible for the conduct of any case court, ie, those involved in the PO trials – including the judges – who were culpable for those repeated failures to comply with clear legal evidential disclosure standards. This omission was surely tantamount not only to professional negligence, but also to a dereliction of their duty to uphold justice (‘Solicitors must act in a way that upholds the constitutional principle of the rule of law, and the proper administration of justice. In a way that upholds public trust and confidence in the solicitors’ profession and in legal services provided by authorised persons’. SRA Principles, SRA Standards and Regulations, the Law Society, 2019).

Bringing responsible legal professionals to account

For the maintenance of trust in the legal profession, and in British justice, it should be of deep concern to and a desire of all solicitors, barristers, legal educators, the judiciary and government administrators of justice that the legal professionals who can be identified were to blame now be brought to account. But how should this vital calling to account of the lawyers responsible be framed and managed?

The Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) states, ‘We are investigating, with live cases into a number of solicitors and law firms who were working on behalf of the Post Office/Royal Mail Group. […] We will take action where we find evidence that solicitors have fallen short of the standards the public expects’ (‘Statement: Update on the Solicitors Regulation Authority investigation on the Post Office Horizon IT scandal’, 19 January 2024). There seems to be no focus in the SRA’s agenda on the key issues of solicitors’ unchallenged reliance on the ‘presumption of reliability’ of, nor of the failure in their duty to disclose, or seek disclosure of, computer evidence – perhaps the SRA has limited experience of the specialist forensic techniques and standards pertaining to professional preservation, disclosure, examination and analysis of computer evidence.

Sam Townend KC, Chairman of the Bar Council, has said ‘There is a case for Parliament to ‘review wholesale’ the role of companies in bringing private prosecutions following the Post Office Horizon scandal’ (‘MPs could review private prosecutions after Horizon scandal – Bar Council chair’, Tom Pilgrim, The Standard, 9 January 2024). Once again, it seems there is no focus on the key issues of barristers’ unchallenged reliance during the trials on the ‘presumption of reliability’ of, nor of the failure in their duty to disclose, or seek disclosure of, computer evidence in the PO Horizon trials.

For the UK government itself, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) has said, ‘The Post Office Horizon inquiry is ongoing but we will consider the findings – including any related to prosecution evidence – once the Inquiry has concluded. […] The Criminal Procedure Rules Committee will consider current practices and potential problems relating to the reliability of computer evidence […]’ (‘Update law on computer evidence to avoid Horizon repeat, ministers urged’, The Guardian, Alex Hern, 12 January 2024). It appears, however, that there are no MoJ plans to address the issue of bringing to account the solicitors and barristers negligently involved in the faulty PO Horizon trials.

As for the judges who presided over the PO Horizon trials there has been no announcement of a proposal to investigate their conduct. Presumably any investigation would come under the following: ‘In cases where the judge’s conduct is seriously impugned, the relevant Head of Division or Presiding Judge will refer the matter to the Lord Chief Justice and Lord Chancellor. This is another way in which individual judges are accountable’ (‘Judicial conduct’, Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, Judicial accountability and independence). If so, this may involve the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office, which ‘supports the Lord Chancellor and the Lady Chief Justice in their joint responsibility for judicial discipline’.

Private remedies: a class action?

Overall, it appears that there is a lack of urgency (‘wait for the outcome of the PO Horizon Inquiry’), or, perhaps, appetite, among legal professional bodies and regulators to address the negligent omissions of legal professionals in the PO Horizon trials, in regard to the key ‘presumption’, and, most importantly, ‘disclosure’, issues, concerning critical computer evidence. So, given that reluctance, perhaps private remedies for seeking redress, from those who can be identified were to blame, are the way to go?

I have been approached by at least one firm of solicitors, experienced in group litigation, and with litigation funding available, to act as expert witness in computer software and evidence, for a putative class action lawsuit against ‘all those responsible for the faulty PO Horizon trials’. Covering at least the period 1999-2019, there could be quite a diverse cast of characters to be legitimately targeted as defendants for such a potential class complaint. This would include executives, managers and staff of the PO, and Fujitsu, plus the various government ministers and civil servants responsible for overseeing postal services; the software design, development and testing engineers of the Horizon system, together with its operational help desk management and front-line personnel; the sub-contractors employed by the PO to ‘audit’ the accounts of sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses; and of course the appropriate solicitors, barristers and judges involved in the trials.

Equally, the class of plaintiffs would also be large, numbered in the thousands. The class would encompass the sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses and their families, plus all those affected and injured by their experiences, by the financial and other damaging consequences of the incorrect ‘audits’, and by the false prosecutions and their outcomes.

Furthermore, analysis by The Times estimated that by the end of March 2024, the taxpayer-owned and funded Post Office had likely spent £390 million in legal costs, twice as much on lawyers’ fees in response to the Horizon scandal as it had paid in compensation to victims. Of course, that analysis needs a fundamental correction: the PO has spent nothing. It is British taxpayers who footed the bill for the hundreds of PO private prosecutions over 20 years, and the government has latterly committed taxpayers to shelling out yet further hundreds of millions on more lawyers, an inquiry and compensation to the PO victims. But – reality check! It is surely those who were actually responsible for the fraudulent prosecutions, and benefited from them, who should be corporately and/or personally paying for all this. Taxpayers are just as much the innocent victims, and should not be financially liable.

It may well, therefore, be that a private class action lawsuit is perhaps the only realistic and effective solution for bringing all those actually to blame substantively, timeously and effectively to account, and to achieve payment of adequate compensation to all the PO Horizon victims, including taxpayers.

The ‘fossil record’ can identify who was to blame

A challenge for such a class action may be the forensic analysis through which individuals can be identified to have been negligent and culpable. However, the truth lies in the ‘fossil record’ of, yes, the computer evidence. Fujitsu’s and the Post Office’s (and others’) computer records will have details and data from which an experienced professional forensic IT expert can objectively identify who was responsible for what, who managed whom, who made what decisions, when and why, etc. As well as the business, management, accounting and personnel records held in the relevant corporate computer systems (and in the software and systems repository for the Horizon development, deployment, help desk, etc, itself), there will also be relevant digital messaging records in emails and social media. The specialist exercise of analysing all that computer evidence is exactly what forensic IT experts routinely do, and the individuals who were culpable and are legitimately to be blamed are almost certainly identifiable, and could thereby be reliably revealed.

It is interesting that a somewhat resonant class action lawsuit has been launched in the United States on behalf of creditors of the high-profile failed and fraudulent cryptocurrency exchange operator FTX. That class action lawsuit has, unusually, been brought against the 100-year-old law firm Sullivan and Cromwell, seeking substantial damages from the law firm and its partners for its prior involvement with the bankrupt crypto exchange. While the causes of action pleaded, over 75 pages, in that lawsuit may not have exact counterparts in English law, there are several that perhaps could have a common law chime with a UK group litigation against ‘all those to blame’ for the PO Horizon trials.

Here, the culpable lawyers’ professional negligence in failing to disclose, or seek full disclosure of, pivotal computer evidence relied upon by the PO might be legitimately pleaded as a ‘common law aiding and abetting fiduciary breach’ of their duty to uphold justice (see for example https://cointelegraph.com/news/ftx-creditors-sue-sullivan-cromwell-alleging-fraud-involvement; https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.flsd.662461/gov.uscourts.flsd.662461.1.0.pdf).

The UK government must get rid of that faulty ‘presumption’

Returning to the wider, key point of reliance on the incorrect ‘legal presumption of the reliability of computer evidence’, which was fundamental to the ability of the PO to pursue its private prosecutions, the continuing and potentially damaging existence and operation of that aberrative ‘presumption’ needs to be urgently fixed. It is time that the absurd ‘presumption’ be repealed and removed, and the UK government must surely now attend to achieving this as a priority.

This correction need not, and should not, wait for the outcome of the PO Horizon Inquiry. The ‘presumption’ is, and always was, fundamentally legally and scientifically unsound, and should never have been introduced by the Law Commission in the first place. While it persists, the risk of yet further faulty prosecutions, trials and miscarriages of justice, based on unchallenged computer evidence, is ever present. One ray of hope is that, following my submissions to my MP, Rt Hon Dame Priti Patel MP, urging the repeal of the ‘presumption’, I am now in discussion with the Cabinet Office, in particular the Directorate of the UK government’s Resilience Academy (‘Deputy Prime Minister annual Resilience Statement’, Cabinet Office, 4 December 2023).

The duty to disclose all relevant computer evidence must be fulfilled

Furthermore, the critical importance of the duty to disclose all relevant computer evidence at trial needs to be constantly highlighted and emphasised. Academics, instructors and practice professionals involved in the education of law students and the training of new legal practitioners must ensure to embed in their pupils’ heads, hearts and souls the foundational principle that, irrespective of the ‘presumption’, the duty to disclose at trial all relevant evidence, including computer evidence, is fundamental to the pursuit of justice and a fair hearing.

In a world now utterly dependent on computer software and systems, full disclosure of computer evidence is supremely important in litigation and the resolution of disputes. The technically esoteric nature of digital evidence simply has to be faced, understood and engaged with by solicitors, barristers and judges. This may well require the involvement and assistance of independent skilled and experienced forensic IT experts to advise on the elusive nature and intricate details of the technical disclosure pertaining to the case, and then to apply their expertise to be able to examine, analyse, challenge and validate, alternatively rebut, such vital computer evidence in court. Modern British justice demands nothing less, if only to avoid future ‘Horizons’.