Neurotech: an emerging frontier in technology and patents

By Virginia Driver and Sarah Hamburg

Dr Sarah Hamburg from Page White Farrer and Virginia Driver share their thoughts on the patentability of neurotech

As European patent attorneys who advise companies in multiple jurisdictions, we keep a close eye on global market and technology trends. We have noticed significant growth in the field of ‘neurotech’, and consider here the patentability of neurotech innovation. The market opportunity for brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) was recently reported to be $400 billion in the US alone. Investors have commented on the potential to ‘open new realms of communication, rehabilitation and cognitive enhancement.’

Neurotech patents

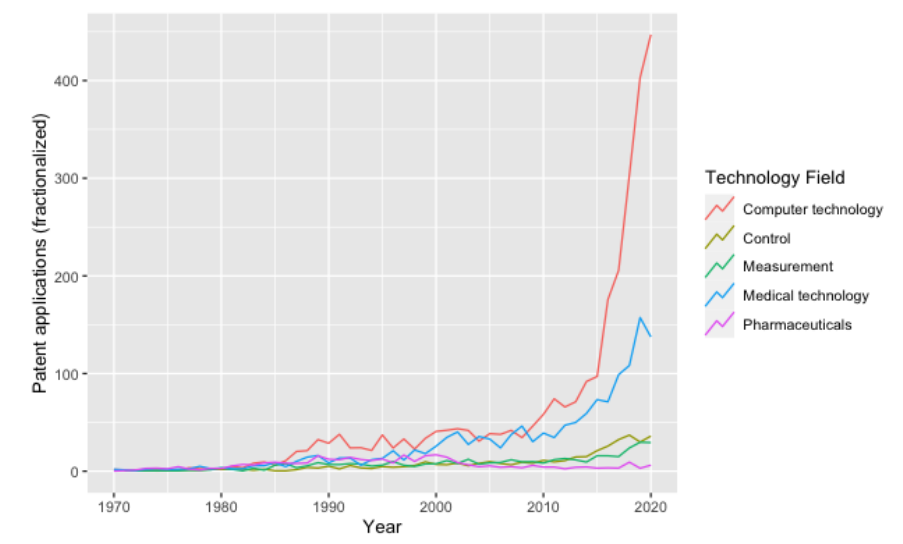

Although there are no specific International Patent Classification (IPC) codes for neurotech, UNESCO recently developed a taxonomy which allows the numbers of patents in the field to be considered. The total number of neurotech patent applications submitted worldwide each year currently exceeds 1,400, with IBM and Microsoft being leaders in this space. Although there has been a recent doubling of annual patent applications for neurotech worldwide, this figure remains a small fraction compared to other sectors (eg, artificial intelligence (AI) applications exceed 90,000 each year).

It is unclear why, for such a high-value space, the number of patents should be so (relatively) small. In principle, innovations in the neurotech space are very likely to satisfy the core patentability requirements of novelty, an inventive step and a technical effect.

BCIs are a form of neurotech that enable direct communication between the brain and a device, such as a computer mouse or robotic arm. Other forms of neurotech include neurostimulation and neuroimaging devices.

Neurotech is not a new field. Last year marked the 100th birthday of the first ‘EEG’ recording of the brain’s electrical activity. Many neurotech devices still use the same technology today. Key milestones include the first deep brain stimulation to treat Parkinson’s disease in 1987, and the first human to control a mouse with their mind using implanted electrodes in 1998. A quarter of a century later, last year saw the first human to be implanted with Elon Musk’s Neuralink device.

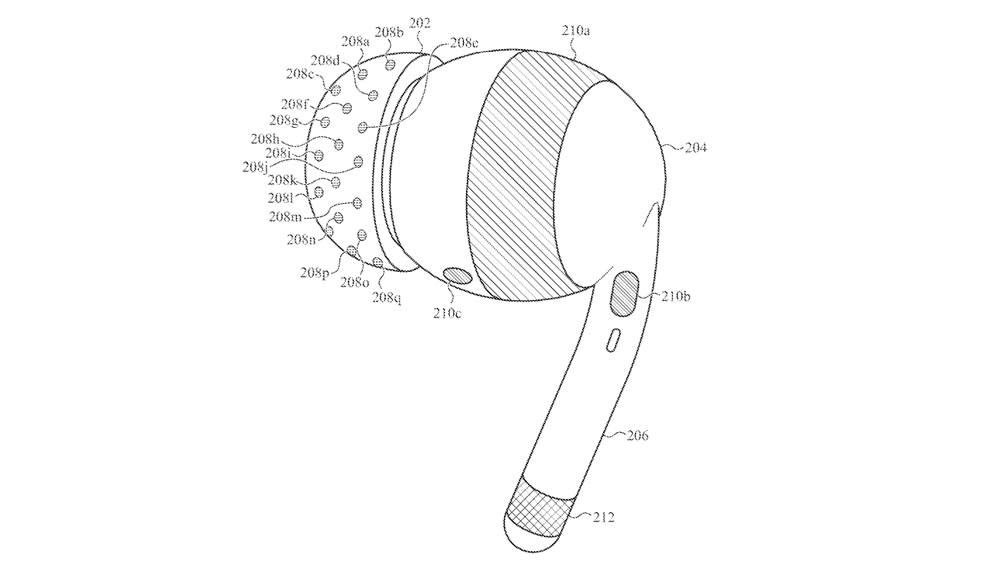

The market has recently experienced a rapid rise in consumer-focused home-use devices, including Samphire Neuroscience’s nettle device for menstrual health, Flow Neuroscience’s depression treatment used by the NHS, and Nurosym’s vagus nerve stimulator. Apple’s pending AirPod patent, featuring sensors for EEG signals, shows neurotech is poised to enter our everyday lives.

Apple’s patent also seeks protection for measuring signals from the eyes, heart and skin. This is a powerful combination which could potentially provide AirPods not only with eye-tracking capabilities, but with a form of mind reading. While this may seem farfetched in regard to a headphone, eye movements can reveal cognitive processes, and heart and skin signals underlie lie detector technology.

It is undoubtedly an interesting time for neurotech. Solutions are well-positioned to take advantage of advances in AI to solve many of our most pressing health challenges, particularly where pharmacology has failed, from neurodegeneration to improving mental health. Neurotech is also uniquely placed to potentially solve one of the most pressing challenges of future generations, AI alignment (many people believe that neurotech offers a path to merging our brains with AI, preventing humans from being dominated by AI systems).

Emerging technologies, including quantum sensors, may further revolutionise existing neurotech solutions. For example, the neuroimaging technology, magnetoencephalography (MEG), is limited by the requirement for super-cooled cryogenic sensors. However, the British company, Cerca Magnetics, has recently developed MEG technology leveraging quantum sensors (OPM-MEG system) to overcome these limitations.

A breakdown of neurotech patents by technology field reveals that computer technology experienced a breakout to prominence around 2010. This reflects growth in neural computing techniques, which form part of the neurotech landscape. The overall report concludes that a neuromorphic computing cluster holds significant importance and provides valuable insight into the impact of neurotech on computer technology and AI.

Importantly, neurotech inventions require careful navigation of the patenting system. For example, a brain stimulation technique for treating depression would benefit from claims directed towards the device or apparatus itself, and the computer-implemented method controlling the device, rather than the method of treatment (methods for treatment are excluded from patentability in Europe). Similarly, a patent for an invention whereby a user controls a prosthetic limb by imagining its movement would benefit from claims that focus on the technical system itself, as methods for performing mental acts are also excluded from patentability.

.jpg&w=256&q=75)

.jpg&w=256&q=75)